History of Georgian chant is directly linked with the introduction and dissemination of Christianity in Georgia. In the 4th century (325) Christianity was state religion, presumably same kind of chanting was common in Georgia as in Byzantium. Today it is difficult to specify when Byzantine melodies were transformed to national ground, but this process could not have lasted long. Basic principle of Georgians musical thinking is polyphony, which completely differs from developed European polyphony. Georgian chant is chiefly three-part, four-part examples are rare. Its polyphony bases on national musical thinking. In Georgian three-part chant canonic tune (cantus firmus) is in top (highest register) voice.

Georgian chant is an inseparable part of Georgian culture; it developed at Monastic Centers in and outside Georgia (Palestine, Mount Sinai, Mount Athos, Jerusalem most distinguished among these was St. Sabbas the Sanctified Monastery, where foundation was laid to Georgian hymnography (7th century). Initially it was presented by the hymns translated from Greek. Translated hymnographic material was collected in ancient Georgian monuments – lectionariums. Several ancient editions of lectionariums (from Kala, Latali, Paris and Mount Sinai), reflect Liturgical practice in Jerusalem from the late 5th century until 10th centuries. In general lectionarium shows three basic types of chant performance: responsorial, antiphonal and single-choir.

First independent hymnographic collection – iadgari (lit. memorable) was created on the basis of lectionariums; it united the chants to be performed throughout a year. Several old copies of iadgari, created before the 10th century, have also survived. They contain unique data about early stages in the development of Byzantine and Georgian hymnographies.

From the 10th century Georgian centers of hymnography suppressed by the Arabs were moved from the Holy Land to other Monastic Centers.

Georgian Literary School on the Mount Sinai played significant role in the development of Georgian hymnography, continuing the traditions of St. Sabbas’ school of hymnography.

Further development of Georgian hymnography is related to the Monastic schools of Tao-Clarjeti headed by Reverent Grigol Khandzteli – great ecclesiastical figure of the 9th century. Khandzteli knew by heart year-round chants and taught chanting. He himself composed a complete collection of chants – satselitsdo iadgari, which provided a basis for further development of original hymnography. From the 9th century, alongside the translation process original hymnographic activities intensively developed and reached the pinnacle in the 10th century. At this time figures such as Ioane Minchkhi, Ioane Mtbevari, Ezra, Kurdanai, Stepane Sananoisdze, Ioane Konkozisdze, Mikael Modrekili and others appeared in national hymnography. This process of development was crowned by the creation of several so-called great iadgari (from Tsvirmi, Ieli and Mikael Modrekili’s iadgari). Particularly noteworthy are great Mekhuri iadgari, which contain ancient chant notation signs – neumes. Introduction of eight-tone system and domination of irmos-dasdebeli (- troparion) form determined application of neumatic notation. At the time appeared a new type of hymnographer – mekheli or a person skilled in troparion science, who translated the examples of early-Byzantine rhythmic poetry into Georgian maintaining the rhythm, adjusting the mode (tune) of the original verse to Georgian text. Noteworthy among Mekhuri iadgari is Mikael Modrekili’s “Satselitsdo iadgari” (S-425), in which systematized is entire hymnographic heritage –both translated and original hymns of Georgian and Byzantine hymnographers. The collection created in 977-988 is supplied with neumes.

Most powerful center of Georgian Christian literature and music is Monastery of Iviron or Iveron at the monastic state of Mount Athos. The founders of this school were fathers Ekvtime and Giorgi Mtatsmindeli, their names are related to the new stage of Georgian hymnography, when elaborated were new principles for translating hymnographic works. The Fathers from Athos translated most important hymnographic collection from Greek, most distinguished among these was Giorgi Mtatsmindeli’s “Ttueni”, in which the author collected the chants dedicated to different saints by all authors.

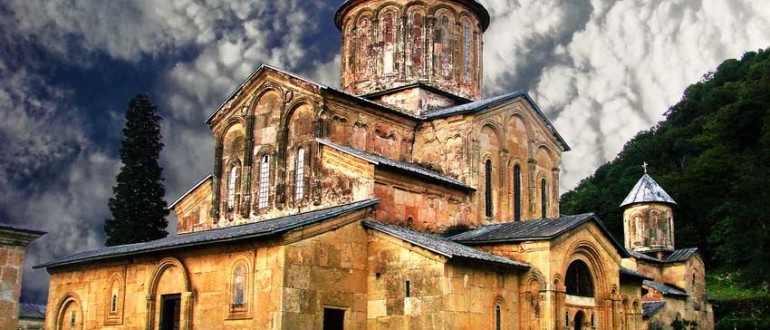

In the 11th century significant literary-philosophical Centre was the Bachkovo Monastery (archaically the Petritsoni Monastery), a representative of this literary-philosophical school is Ioane Petritsi, thanks to whom Georgian literature was more approximated to Byzantine. Petritsi provides the information about the polyphonic nature of Georgian music. He indicates the names of three voice-parts: “mzakhr”( first voice), “zhir” (second voice), “bami” (bass) and writes about the harmony created by the combination of the three. In Petritsi’s opinion three-part singing (or the unity of mzakhri-zhiri-bami) is a musical analogy to Christian Trinity, testifying to three-part singing in Christian liturgy. After Petritsoni Ioane Petritsi continued his activities at Gelati Monastery – principal centre for Georgian church chant from the 12th century until early 20th century.

In 13th-16th centuries due to grave political situation in the country Georgian art of chant started to decline. Hymnographic collections were annihilated at robbed churches, only the monasteries that survived raids, sheltered Georgian chants. Despite this, for Georgian chant the process of natural development continued very slowly. To this testify the surviving to this day 17th-18th -century hymnographic collections, including hymnographic and stavropigial readings with liturgical indications. These collections help us create an idea about the hymnographers such as Nikoloz Maghalashvili, Grigol Cherkezishvili and others. National elements prevail in the works of these hymnographers.

It is known that in Georgia turning process, that cultural development started from the turn of the 16th-17th centuries and Gareji monastic complex played particular role in this. Ecumenical Council called on 12 march, 1690 by King Erekle I elected Onopre Machutadze Prior of the Monastery (1690-1733). The number of writers, preachers, chanters, calligraphers, etc increased at Gareji Monasteries during this time. Exactly at this time Gareji became one of the most important centers of Georgian spiritual culture. It is also known that Mravalmta monasteries of Gareji boasted particular patronage and support of the Royal court. Literary and historical sources write about a school of chant for 7-10-year old children at Gareji. The studies continued 5-10 years. Similar to developed Middle Ages the students received multilateral education and grew up as bibliophile-chanters, among the alumni were Catholicos Anton I, Ambrosi Nekreseli – an accomplished writer-bibliophile- chanter; Germane Khutses-Monazoni – a wonderful preacher and chanter at Dodo Monastery; Archimandrites Geronti Sologhashvili who taught literature and chanting at Gareji, and others.

At the end of the 18th century King Erekle II took the initiative to preserve traditions of Chant Schools. For this purpose founded was Catholicos’ School, where renowned chanters from different parts of Georgia were specially invited to teach. In Georgian history this period of reanimation did not last long. Abolition of the autocephalous status of the Georgian Church (1811) and introduction of the Divine liturgy in Russian language (with Russian chanting), was a great threat to the existence of centuries-old Georgian chant. From the second half of the 19th century battle for the preservation of Georgian art of chant was renewed. For this purpose Georgian chants were transcribed to Western five-line notation system, thus preventing them from being lost forever. Saint Bishops: Gabriel Kikodze, Alexandre I (Okropiridze), Saint Karbelashvili brothers: Pilimon, Polievktos, Stepane, Petre and Andria, St. Ekvtime the Confessor (Kereselidze) and St. Pilimon (Koridze), Deacon Razhden Khundadze, Priest Anton Dumbadze, Dimitri Chalaganidze, Ivliane Tsereteli and others greatly contributed to the preservation of Georgian chant. Also noteworthy is the merit of Khristofor Grozdov, Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov, Nikolai Klenovsky in the documentation of Georgian chants. Thousands of chants transcribed by them are preserved at the National Centre for Manuscripts.

In early 20th century Georgian chant and spirituality in general faced another danger – totalitarian regime which attributed to religion the title of bhang for people and carried out severe battle against it. During certain period Georgian chant was lost for Georgian society.

In Soviet epoch there was practically no divine liturgy at the churches, chanting nourished from various sources (Russian chant, opera and city music) was basically heard at Sioni Cathedral Church. From the late 1970s this music was partially replaced by three-part hymns in traditional mode and harmony composed by a brilliant master of choral music – Ioseb Kechaqmadze at the request of the catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia Ilia II. Certainly these were not medieval hymns created according to the eight-tone composition system. This was an attempt to hear qualitative music of a professional musician instead of low quality one.

Works of different secular composers on different sacred texts were heard in Soviet epoch churches, they based on European major-minor system or were stylized variants of Georgian folk mode-harmony and were completely devoid of canonical basis of chanting.

Renvival of Georgian canonical chanting started in the 1980s, when the members of Anchiskhati church choir started to chant ancient tunes from the handwritten scores of Georgian chants preserved at the archives of National Centre for Manuscripts. Currently, according to the order of the Holy Synod of Georgia Divine Liturgy at Georgian churches is carried out as accompanied only with ancient Georgian canonical chants.