A field expedition to the town of Akhaltsikhe and three villages in Meskheti-Javakheti was organized on 16-30 July, 2005, as part of the UNESCO program. The expedition included Tinatin Zhvania and Ketevan Matiashvili from the IRCTP, and Conservatoire students Nana Gogoladze, Baia Zhuzhunadze and Nino Naneishvili.

There had been no musical examples from Meskheti-Javakheti among the expedition recordings preserved at Georgian Folk Music Department. The material recorded in this province of Georgia by Shalva Mshvelidze’s expedition in the early 1930s, which has recently been transferred to digital media under the IRCTP project, will significantly enrich our knowledge of the musical folklore of this region. No less valuable is the material obtained by our expedition – 9 mini disks (150 minutes each) and 1056 photos.

Mshvelidze’s expedition was the first to Meskheti-Javakheti; the second expedition was led by Grigol Chkhikvadze in 1949. The intensive expeditional work performed by composer Valerian Maghradze is also noteworthy.

For better understanding the musical and ethnical picture of this part of Georgia, we find it appropriate to say few words about some facts from the past.

Historically the territory of Meskheti-Javakheti was the South-West part of the Kingdom of Iberia. It was an inseparable part of the province of Kartli. Its population were ethnic Georgians; they spoke Georgian language and did not differ from the population of Shida Kartli and Kvemo Kartli in their anthropological type, everyday life and traditions.

Political, social, religious and ethnic upheavals have changed this region much since the 13th century. After Turkish and Persian invasions the process of conversion of local Christian-Orthodox population into Islam accelerated. This resulted in mass exodus of native population from here to other parts of the country. At this time Turk-Selchuks and Armenians started to take up their residence on Georgian lands. In time the congregations of Catholic and Armenian-Gregorian churches started to enlarge at the expense of the locals. Nevertheless, a small part of the Georgian population managed to maintain their links with Orthodox traditions.

At the beginning of the 19th century 100,000 Armenian refugees were resettled from Erzerum; they were followed by Kurds, Greeks, Dukhobors, etc.

In 1944 Turkish-speaking population, the so-called “Turkish Meskhetians”, was exiled from Meskheti-Javakheti. From this time on, Georgians from various parts of the country (Imereti, Achara, Svaneti, etc.) moved here and found their home.

In 1960 Grigol Chkhikvadze wrote: “Both expeditions (Mshvelidze’s in the early 1930s and Chkhikvadze’s in 1949) carried out very fruitful work. They did not collect much, but what they did, was truly precious. The character and content of the collected material, though poor, makes us believe that more careful study will allow us to find significant examples that are linked to the centuries-old life of our people . . . ” (G. Chkhikvadze, “Georgian Folk Song”, 1960, pp. 21-22).

The same can be said today. Based on the information, obtained from 46 ethnic sources, it can be concluded that true Meskhetian folk art has barely survived. Instead, you can often hear both young and elderly people sing the town songs from East Georgian town folklore such as Saiatnouri, Baiati, Ietim Gurji and others.

In Akhaltsikhe we met the leading expert on Meskhetian musical traditions, now deceased, Shota Altunashvili. He taught many already forgotten Meskhetian songs to many people. The repertoire of his ensemble Meskheti included many Meskhetian songs arranged for three voices. As Altunashvili told us, people had sung those songs in one voice. Among the one-voiced examples we recorded from him were Otkhi Tsqaro Sdis, Mravalzhamier, Gegutisa Mindorzeda, Vardzioba-Dziobasa, etc.

We sorted out the expedition material according to the parameters characteristic solely for this region. One of these is collection of all type of information connected with the tradition of multi-voiced singing, which is considered to be lost in Meskhetian life. The most noteworthy statements connected with this are mostly about the function of bass voice part, such as Banze Adevneba (i.e. tuning low voice to the melody, etc).

When talking about the ensemble of instruments popular in Meskheti-Javakheti in the past, Zurab Ivanidze (81) from the village of Atsqvita said that the instrument chichila (also called mei) was used for bass, or when 3-4 tulumis – Meskhetian name for gudastviri (bagpipe) – were played together, one of them would be in the function of low voice.

The most important findings of the expedition are the examples, once very characteristic for local musical life, such as Orovela that we recorded from Giorgi Jinchveladze (97) in the village of Muskhi. It should be mentioned that this song is similar to Kartli-Kakhetian songs with the same name in its mode-intonation and composition.

As for the other, it is once very popular dance performed with dancing and singing with glossolalias Dam Dalili Dillilo . . . We must say that like Orovela, this song is also fairly close to Kartli-Kakhetian dance melodies. We recorded a very original three-voiced variant of this example from Mito Taturashvili (63) in the village of Khizabavra with accordion accompaniment; he played middle voice and bass on the accordion.

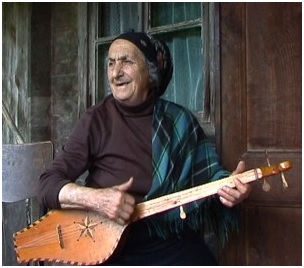

Very precious information on old Meskhetian repertoire we obtained from Mariam Zhuzhunadze (73), a good connoisseur of Meskhetian traditions, in the village of Muskhi. We would separately mention the information about the form and tradition of performance of the Meskhetian round-dance song Okromchedelo. Mariam assiduously taught both the song and round dance to the members of the expedition.

The stviri, a one-piped wind instrument with finger-holes, has still been used in everyday life as the echo of old Meskhetian traditions. In all three villages there are people who make and play this instrument. We documented the rules for making stviri from Vazha Melikidze (63) and Vaso Ivanidze (65) in Muskhi, Giorgi Diasamidze (78) and Ilusha Ivanidze (78) in Atsqvita, and Mito Taturashvili in Khizabavra. In all these stories the rules, number of finger-holes, their places on the pipe and musical-intonational content are similar. This testifies to the fact that the old Meskhetian tradition of this instrument, which used to be an inseparable part of cattle-rearing, the main farming activities of this region.

Now about the most characteristic repertoire of Meskhetian musical life today: although today you will rarely hear the sound of zurna, duduki, doli and garmoni , that once penetrated into Georgian villages from towns, but in Meskheti they are still used. In Atsqvita, for instance, almost every family has their “musicians”, who sing and play together at the wedding parties and other festive occasions. For some objective reasons, we were not able to bring them together. We managed to record Oleg Ivanidze (46) – a member of one of such ensembles. Together with his son and wife he sang modern-type songs from the so-called wedding repertoire, such as Ra Lamazi Khar Shen Tushis Kalo, Rotsa Shen Dalalebs Kari Shlis, Sichabuke Da Akhalgazrdoba, etc.

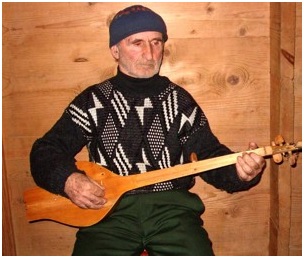

Special mention should be made of Mito Taturashvili from Khizabavra – a virtuoso instrumentalist from the circle of “wedding musicians”, who brilliantly plays duduki, zurna, clarinet, various types of salamuri, panduri and accordion.

As mentioned above, many people of various nationalities lived and still live in Meskheti. It is a well-known fact that local Georgians have always had friendly and neighbourly relations with them. More than 60 years have passed since the Turkish population left this region, but those who had good relations with them, still remember Turkish language and songs.

Particularly interesting in our opinion is the rule of reading fairy tales that we recorded from Aniko Zhuzhunadze (71) from Muskha and Zurab Ivanidze (81) from Atsqvita. Here Georgian and Turkish episodes take turns. Also interesting is that the verses to be narrated in Turkish, they sang in Turkish manner. It turned out that in the past these verses used to be accompanied by oriental stringed instrument saz.

As it is known, Akhaltsikhe is an international town. The respect between various nations towards each other is revealed in the ethics of instrumental ensembles as well. For instance, at wedding parties and other occasions the repertoire of Georgian and Armenian instrument players is represented with the characteristic examples of these two nations.

We were very much impressed by the trio of Armenian instrumentalists from Akhaltsikhe: Arsen Melikian (45) – duduki, zurna and clarinet, Khachatur Akopian (45) – accordion, and Garegin Geian (71) – daira, doli and vocal. They performed the Armenian melodies Pepo, Mtvarian Ghames and Eghishis Tsekva, and a Georgian song with instrumental accompaniment, Tsiv Zamtarshi.

We believe that the field expedition of 2005 in Meskheti-Javakheti should be followed soon by intensive field work in this region, due to the fact that most folk musicians in this region are quite elderly. There is an urgent need to document these musical traditions before they disappear.