As part of UNESCO program, the International Research Center for Traditional Polyphony carried out a field expedition in Sagarejo district on August 17-30, 2005. The participants were Nino Makharadze and Lela Makarashvili, faculty at the Conservatoire’s Georgian Folk Music Department.

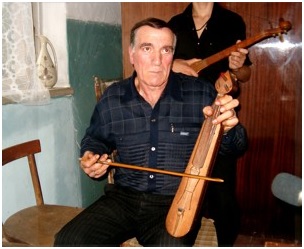

The majority of the material recorded on this expedition includes instrumental pieces played on panduri in the style of East Georgian mountain repertoire (such as Stirian Tushis Kalebi, Mtashi Salamurs Vakvneseb, Vazhkatso Mtashi Gazrdilo, Shirakshi Ertma Metskhvarem, Shatilis Asulo, etc.), variants of Kakhetian shairebi (humorous songs), dance melodies (Kakhuri, Lekuri and Osuri) and popular Acharan melodies.

Verbal material, collected together with folk examples, testify that the traditional rituals are performed here in the same way as elsewhere in Kakheti. These rituals include those for healing children’s acute contagious diseases (such as mumps, measles, scarlet fever, chicken pox, whooping cough, etc), other rituals including Eliaoba, Alilo, Dideba, Berikaoba, and the weather ritual of plowing water with a plow.

In the village of Tokhliauri we recorded lamentation with verbal text during a funeral. We collected the examples of song and instrumental music, description of various rituals, information on farming activities from senior citizens Nikoloz Kupatadze, Tamar Mekaluashvili, Aleksi Matiashvili and Zhuzhuna Shioshvili. Lamzira Zakaidze, the director of the local house of culture, leads a women’s ensemble and makes every effort to encourage youngsters to sing. Her group sang a few songs for us, including town songs with guitar accompaniment.

We recorded a few songs with panduri accompaniment from Neli Bugechashvili, whose family is originally from Pshavi. She also told us about the religious holiday LasharisMtavarangelozobis Khatoba and about some wedding rituals in Ukana Pshavi. We filmed children’s games in the same village.

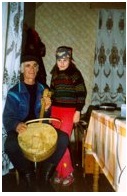

Our meeting with an elderly couple Tamar Natsvlishvili, born in 1926, and Nikoloz Tatarashvili, born in 1925, was unforgettable. The husband and wife have restored the local church with their own means, and are taking care of it. From them we recorded blessings, toasts, salamuri tunes, dance melodies and an Iavnana melody played on panduri.

We learned, that on the 3rd and 4th Sundays after Easter, the festival of Kalobnoba is held at the St. George and Virgin Mary churches near the village of Tokhliauri. Many people come here from the neighbouring villages too. The banquets on these days are accompanied by wrestling, horse racing, dancing and various games. The villagers have their summer pastures on the Mount Tsivi. According to Nikoloz Kupatadze local shepherds still make their salamuri from the black elder tree. Sadly, on this visit we did not meet any of the shepherds.

We also visited the villages of Ninotsminda, Giorgitsminda, Manavi, Kakabeti and Udabno.

Thanks to Maia Aleksishvili, director of the Ninotsminda house of culture, we managed to meet local panduri players Vasil Rochikashvili and Shalva Akhverdashvili. They gladly accepted our request and played humorous songs and dance melodies for us. Kalia Rostomashvili, famous local singer, agreed only to tell incantations, as she was in deep mourning. In the hospitable family of Nadia Ivaniashvili, we recorded the song-lamentation sung by Eliko Gogaladze-Rostomashvili, born in 1941. The song is dedicated to the soldiers who fought and died in Abkhazia.

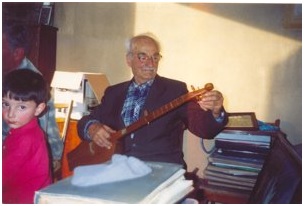

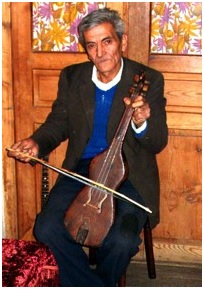

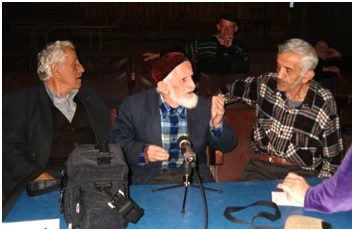

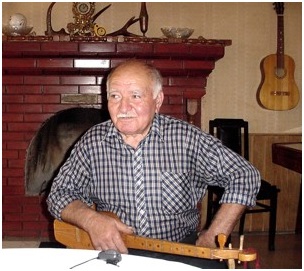

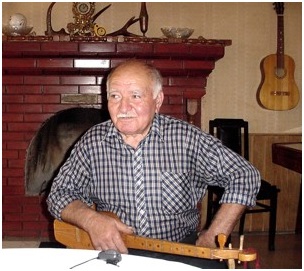

In the village of Kakabeti we met Ushangi Masurashvili (78) and Mikheil Galustovi (76). These elderly people used to sing in the well-known choirs of Mikha Jighauri and Vano Mchedlishvili. Together with well-known songs, such as Berikatsi Var, Tsintsqaro, Chonguro, Orovela, Iavnana, Herio and Garekakhuri Sachidao, we recorded fragments of Kakaburi Mushuri and Alilo, dance melodies, humorous songs, Soviet and town songs performed by them. At the initiative of Niko Gigoshvili, director of the local house of culture Ushangi, who is a chonguri master too, teaches traditional folk songs to his grandchildren and other young people. Niko has a small collection of musical instruments and a very interesting photo, audio and video archive. Dariko Mirziashvili, a wonderful panduri player, directs children’s and women’s ensembles in the village.

The festival of Berikaoba is held annually in the village of Chailuri. We think that this event should be filmed soon. For the next expedition we are planning to visit elderly singers and poetic storytellers, settlers from Pshavi, in the village of Kochbani.

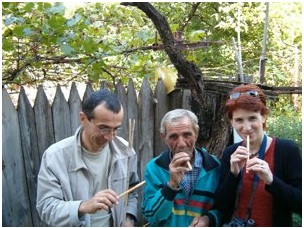

Kako Peikrishvili form the village of Manavi is a member of the local instrumental ensemble which is often invited to weddings and funerals. He plays several instruments such as panduri, doli and duduki. We recorded songs with panduri accompaniment from him including Shakara; variants of this song were very popular in many villages of this district and were documented by Joseph Jordania’s expedition in 1980.

In Manavi we also recorded Nadia Machuridze and Aniko Ekvtimishvili. The two ladies told us about the rules for the ritual of Eliaoba, sang the two-voiced variant of the healing song Iavnana and songs with panduri accompaniment. Ruizan Sonashvili, who is originally from Saingilo (formerly in Georgia, now Kakhi district of Azerbaijan) and is married to a local man, sang Ingiloian lullaby Dai Dai.

We think special attention should be paid to the folk traditions of the village of Udabno. This village was founded in 1984 and is inhabited by the families of migrants from various parts of Georgia including Svans, Rachans, Megrelians, Meskhetians, Ingiloians, etc. During this expedition we visited families from the village of Latali in Svaneti, and recorded Zari, Tsmindao Ghmerto, Jgriagish, Barbal Dolash (a variant form the village of Becho), Irinola-Marinola and Vitsbil–Matsbil as sung by Otar Parjiani, Gunter Pitskhelani, Mirza Ivechiani, Petre Nansqani and Rostom Girgvliani.

The families from Svaneti keep strong links with their home region high in the mountains. They always participate in all summer festivals in Svaneti and do their best to maintain their ancient traditions in Udabno. They are often asked to sing Zari at the funerals regardless the original district of the mourning family. The future changes going on in their musical folklore should be observed.

On 28 August, on Mariamoba (St. Mary’s Day) we attended the church service at Dodo Garejeli church in Sagarejo, and had very interesting conversation with chanters at Dormition of Mary church.

We took a number of photos of panduris (mostly called chonguri by the locals) made of various materials such as acacia, mulberry and pear wood.

We would like to thank Tinatin Mezvrishvili, director of Sagarejo House of Culture, and all those who assisted and supported us in our work.